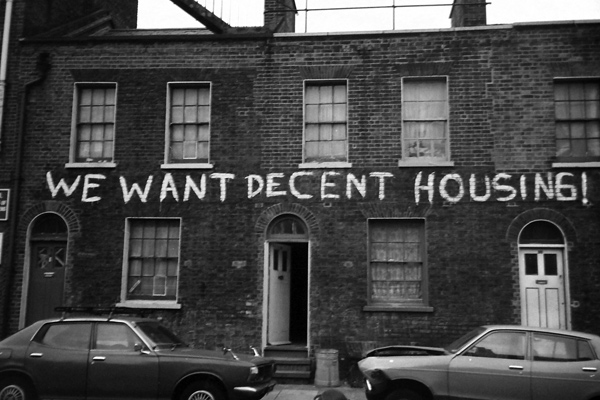

There has been much talk in the press recently about London’s housing crisis and this is set to be a hotly debated issue as the election campaign goes into full swing during the Autumn conference season. I am always wary of the term ‘crisis’ as it suggests major surgery or state intervention are required. It is clear to many property professionals that policy makers manipulate the market at their peril, potentially enshrining ideological ideas into law that might be relevant now, but later become entrenched and politically difficult to change. For example rent controls introduced in 1914 to help the First World War effort lasted until 1989, reducing the private rented sector from 90% to 9%. There is no doubt that there are a lot of frustrated people in London not getting what they want from the housing market, I’d like to take the long view and analyse some of the causes of London’s situation.

There has been much talk in the press recently about London’s housing crisis and this is set to be a hotly debated issue as the election campaign goes into full swing during the Autumn conference season. I am always wary of the term ‘crisis’ as it suggests major surgery or state intervention are required. It is clear to many property professionals that policy makers manipulate the market at their peril, potentially enshrining ideological ideas into law that might be relevant now, but later become entrenched and politically difficult to change. For example rent controls introduced in 1914 to help the First World War effort lasted until 1989, reducing the private rented sector from 90% to 9%. There is no doubt that there are a lot of frustrated people in London not getting what they want from the housing market, I’d like to take the long view and analyse some of the causes of London’s situation.

London’s population is expected to increase by 1 million over the next ten years. We forget that between 1936 and 1984 population was in decline. By the 1970s there was a substantial supply of social housing, peaking at around 32%. Inner city districts like Notting Hill, Islington, Fulham and the Docklands were run down, with streets of Victorian houses desperately needing modernisation. Rent controls had disincentivised the few private landlords that remained from investing in properties. Often tenants refused improvements as they did not want the Rent officer to reassess their rent to a higher level. Thatcher’s Right to buy policy enabled council tenants to buy their homes at a sizable discount, but without allowing local authorities to reinvest the proceeds of sale. So the quantity of social housing stock diminished. Subsequent governments failed to build adequate new homes and very tight planning regulation made new private house building sluggish. There were two key developments in the 1980s. Firstly, the deregulation of the City of London enabled a vast increase in the volume of activity and sported a new generation of high earning executives living in the capital, many ploughing their bonuses into property. Secondly, urban living started to become more fashionable. Waterways, shunned for decades, were cleaned up and became a focus for regeneration, partly funded by taxation from the buoyant financial hub. The introduction of buy to let mortgages in the mid 1990s, coupled with a concern about the viability of pensions and mis-selling of endowments, led to a new breed of investors buying property in the capital. There is no doubt that although buy to let makes up just 14% of mortgages, landlords have competed with other buyers. House buying was certainly fuelled by very active lending by banks – new to the mass market residential mortgage sector – and building societies became increasingly sales driven, spawning sub-prime and buy to let lending arms. London’s population continued to rise, partly fuelled by a generous open doors policy to the ascendant EU countries post 2004, but also because the Prime Central zone of Mayfair, Chelsea and Belgravia was becoming increasingly attractive to wealthy overseas investors.

The 2008 credit crunch and subsequent crash did have an impact on London prices which fell by an average of 16%. Although UK mortgage lending had become very tight post credit crunch, sterling fell and overseas investors saw London as a safe haven and a cheap investment. So by the end of 2009, the housing recovery had already begun. The 2012 Olympic & Paralympics games put the global spotlight on London, making it a fashionable thriving international city where now new build flats were being actively marketed to foreign investors. Areas such as Islington, Notting Hill and Richmond were now considered prime. Hotspots in zone 2 such as Hackney, East Dulwich and Acton were starting to push many people into zones 3, 4 and beyond. The reduction of subsidised social housing has forced many key workers and low earners out of central London. Whilst unemployment remains relatively low compared to EU partners, it is at the expense of low wages often pegged close to the minimum wage and languishing over the past few years below the rate of inflation. Welfare changes have also affected some 40,000 families in London. The benefit cap of £500 per week means that families with two children or more out of work and living on benefits have been forced to move out of inner London boroughs, in some cases to Margate, Hastings, Milton Keynes, Stoke on Trent, Leicester and other more affordable cities. New houses and flats are being built in London, but they are often marketed at investors and there is a very limited number of affordable homes. Moreover they are drip fed into the market to avoid depressing prices, leaving an estimated 15-30,000 shortfall of new properties each year. London is an incredibly successful city economically, set to support this 1 million population growth over the next decade. New infrastructure like Crossrail is geared towards meeting this expansion and also helps create more demand. In the last 12 months Londoners gave birth to 106,000 babies and demographically the Greater London region continues to be the youngest in the UK, attracting students to the many universities based here and young EU migrants keen to launch a successful career or pick things up from where they left off in their depleted southern European place of origin.

So what are the solutions? Many commentators want to blame a particular sector like landlords, foreign investors or developers and punish them with regulation. The problem is the context that has been created by a whole range of policy decisions over the past 30 years. Right to buy, a low tax environment, holding the Olympics in London, de-regulation of the city, the minimum wage, failure to build homes, tight planning control, some open door EU immigration, buy to let mortgages, the pensions offer. Which policy would you turn back? Of course we have to look forward. Here are some of the solutions that have been proposed.

The solution you are most likely to hear is to build more homes. More social housing would have to be funded at least partly by government and private development is severely restrained by planning. Britain is a nation of nimbys and I think there is little hope of planning being eased within the next generation or so. BBC Radio London put forward a number of solutions in its recent housing series, which included building more homes on brown field and green belt sites, coupled with the complaint that developers landbank with a view to building homes at a time that might yield optimal profit. Just how could we free up more brown field and green belt land and is it ethical to force landowners to build on what is their land to do with what they will?

Empty land is indeed akin to an empty property, of which it is estimated there are over 80,000 in London. After two empty years, property owners can be charged a 100% premium on their council tax, but many London boroughs do not implement this charge. Empty property officers across London are doing want they can with grant incentives to get owners to refurbish or rebuild derelict properties and bring them back into use. With such massive housing need, it’s difficult to argue that properties can be left empty in our city. But getting a property from empty to occupied can be a laborious process. Similarly troublesome is the issue of under occupation. In the BBC London series, Lord Best from Hanover Housing proposed that older people be encouraged to downsize into purpose built smaller properties. This is another slow burn solution that requires careful cajoling and supportive management, downsizing is not the favoured option for every older person. Again we hit the civil liberties issue of the older person’s right to stay in their family home – full of memories and extra capacity for family gatherings – whatever its size. Downsizing is not a concept that translates well across cultures where for many, extended family plays a continuous roll.

Changing the rental market is becoming a common proposition as we move towards the 2015 general election, with German style renting topping the list of proposals. German tenants enjoy lifetime tenancies and indexed annual rent rises. This contrasts with 6 or 12 month tenancy agreements in the UK and largely free market rents. The private rented sector now forms 17% of housing in the UK and 26% in Greater London rising to 37% in some boroughs. Many tenants who would have been placed by local authorities in the social sector are now placed in the private rented sector. London’s 300,000 landlords house a wide cross section of the population from students to families, sharers and young and older professionals. The key flaw in the suggestion of German style renting is that the situation in Germany is so fundamentally different to the UK. With 50% of people renting and in some cities like Berlin as many as 90%, Germans don’t aspire to own their homes in the way that the UK population does. This means that house prices are under much less pressure, rises are modest and rents reflect this by remaining relatively stable. In Germany, people generally rent shells and install their own kitchens and bathrooms. Over half of rented properties are owned by institutions and many are recent post second world war structures – there are no rows of terraced Victorian houses which characterises London streets. So this wouldn’t be so much the importing of an idea, it would be the importing of a cultural paradigm. Importing just the rent control and longer tenancy dimension would also have a negative impact. In the current UK system the average tenancy lasts around two and a half years and 90% of tenancies are ended by the tenant. 75% of landlords have no plans to increase rents over the next 12 months and most only do so when new tenants move in. The system is flexible to meet the needs of landlords and tenants and that’s why it is expanding so healthily. Regulation will restrict growth. Would you let your property if you knew it had to be for a minimum of three years? The thousands of accidental landlords who let a property because they had to move for work would fall out of the market, not to mention the lenders who requires a maximum tenancy length of 12 months. In Germany, it’s very hard for an individual to get a mortgage, the lending environment is completely different.

The other overseas example that is often proposed is New York style ‘rent control’ and ‘rent stabilization.’ The former is similar to regulated rents in the UK which only apply to pre 1989 tenancies. In New York, rent control applies to pre 1974 tenancies, that’s 1.8% of residents. Rent stabilisation is a complex model which only applies to certain levels of rent and is subject to means testing of the tenant and only applies to blocks of six or more apartments. Critics argue that these controls have stifled investment, supporters say they have helped maintain the diversity of the city’s population.

The current government has already put forward proposals to slow foreign investment. The effective tax rate that foreign investors pay in the UK averages at 9% according to Savills. That compares with 26% in Hong King , 19% in Singapore and 18% in New York. It is likely that CGT will be due on purchases made by foreign investors from April 2015, due once they sell. This along with the rising pound and a possible mansion tax proposed by Lib Dems and the Labour Party is very likely to slow foreign investment in London. The result will be more properties for domestic buyers and less pressure on sales and rental prices.

Ditching Help To Buy would actually have limited impact in London where only 5% of transactions have used the scheme, which has been most successful for new build purchases outside of London and the South East. However Help To Buy is an example of one stimulus too far by the combined efforts of the Government and Bank of England. Quantitative Easing and Funding for Lending were two schemes which helped to free up the mortgage market and I would argue that it was gradually moving back to something we might regard as normality. Several lenders were offering 95% loans at around 4.5 to 5% which is where Help To But loans have been priced. I would argue that failure to let the market shift and repair without excessive intervention is contributing to market distortion. Although we have seen steep annual house price rises topping 20% in Greater London, this has been largely because of foreign investment and the lack of supply, both of new build homes and the general public putting their house up for sale. The Mortgage Market Review has put the brakes on lending which declined for five subsequent months, before regaining traction again in July 2014’s lending figures. We are also now seeing an increase in supply, these factors only with fears of interest rate rises are causing price increases to subside.

Many people argue that too many new build homes in London are targeted at the luxury market and that we need to see more affordable homes. £627 million were allocated to affordable housing in London between 2011 and 2015 through the Affordable Housing Programme. The programme is making up for the lack of house building in the previous three decades and investment will need to continue at and beyond this level if it is to have any impact on London’s housing situation.

The London Rental Standard is aimed at driving up standards across the capital by getting up to 100,000 landlords accredited. This is a hugely ambitious aim, I hope we will get to a point where tenants opt for an accredited landlord instead of a non accredited one. The scheme will need much greater promotion if we are ever to achieve this aim and the pressure it could put on landlords to improve standards.

Buy to let mortgages are often criticised by the anti landlord lobby and some suggest ending them altogether. About 4 out of 10 landlords have buy to let mortgages, so there isn’t a direct correlation between the reduction of finance and the reduction of the private rented sector. However, a restriction on loans would likely cause a reduction and have an impact on the availability of rented housing as well as a reduction in activity in the construction, financial services and estate agents sectors. There is an assumption that properties that would have been bought by landlords will be bought by first time buyers, but this doesn’t necessarily follow. Ending buy to let or other measures that restrict or reduce the private rented sector could cause a reduction in house prices, a lot of negative equity and a big headache for policy makers.

The final question about solving London’s housing crisis is how much faith we have in our policy makers and institutions. Politicians are of course short termist in perspective, often dreaming up populist policies, drafted for them by an organisation that leans towards one side of the argument. I am concerned about how many politicians have a good understanding of housing, especially as they may take on the portfolio for a matter of months. Our business actually straddles housing, planning and environmental health with finance and economics thrown in and inevitably few politicians have expertise or control over all of these areas. Sometimes I fear politicians push forward initiatives so that they can just be seen to be doing something. There is no one housing market in London, it is in constant flux and initiatives dreamed up are often relevant that week, perhaps timed for a media appearance or an election. Those of us at the coal face of the business may then be saddled with the consequences until the issue becomes fashionable again, which could be many decades later. Cynical as this view may be, I am worried about the policies we might be faced with next year and whether they will be the right way forward for London. I hope politicians will work and listen to landlords.

So what would I do? I’d like to see a massive affordable house building programme in London. I think this, coupled with higher taxes for foreign investors, would have a huge impact over the long term. I would like licensing and article 4 powers to be taken away from local authorities and I’d like to see tax incentives to encourage landlords to become accredited. I’m not averse to a light touch registration scheme – per landlord not per property – that costs around £25 – so that anyone who loses their registration is prevented from managing rented property. I’d like to see more work on empty properties and under occupation and I’d also like to see local authorities keep the proceeds of enforcement action, so that they are incentivised to do more. Each local authority should have a tenancy sustainment and landlord and tenant mediation services too, many already do.

I think German style renting in London is pure fantasy. Introducing rent controls and longer tenancies and reducing buy to let loans would be disastrous. I’d like to see more tenant education, perhaps as part of PSHE in the national curriculum. The new wave of local authority social letting agencies are providing a positive influence, the regulation of letting agents and a shift in culture with less focus on commission, more on the needs of landlord and tenant would be very welcome. Finally, I’d like to see broadcasters show more interest in the landlord perspective. Let’s replace some of the property transformation shows with one or two radio and TV programmes that examine the breadth of housing issues from landlord and tenant perspectives.